BY WALDEMAR KAEMPFFERT

Reprint of article from Feb. 1950,

page 112

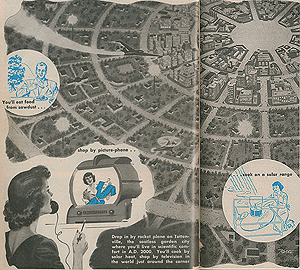

What will the world be like in A.D. 2000? You can read the answer in

your home, in the streets, in the trains and cars that carry you to your work,

in the bargain basement of every department store. You don't realize what is

happening because it is a piecemeal process. The jet-propelled plane is one

piece, the latest insect killer is another. Thousands of such pieces are

automatically dropping into their places to form the pattern of tomorrow's

world.

The only obstacles to accurate

prophecy are the vested interests, which may retard progress for economic

reasons, tradition, conservatism, labor-union policies and legislation. If we

confine ourselves to processes and inventions that are now being hatched in the

laboratory, we shall not wander too far from reality.

|

| In 2000, rocket passengers may arch

through space from New York to San Francsico in less than two

hours. |

The

best way of visualizing the new world of A.D. 2000 is to introduce you to the

Dobsons, who live in Tottenville, a hypothetical metropolitan suburb of 100,000.

There are parks and playgrounds and green open spaces not only around detached

houses but also around apartment houses. The heart of the town is the airport.

Surrounding it are business houses, factories and hotels. In concentric circles

beyond these lie the residential districts.

Tottenville is as clean as a

whistle and quiet. It is a crime to burn raw coal and pollute air with smoke and

soot. In the homes electricity is used to warm walls and to cook. Factories all

burn gas, which is generated in sealed mines. The tars are removed and sold to

the chemical industry for their values, and the gas thus laundered is piped to a

thousand communities.

The highways that

radiate from Tottenville are much like those of today, except that they are

broader with hardly any curves. In some of the older cities, difficult to change

because of the immense investment in real estate and buildings, the highways are

double-decked. The upper deck is for fast nonstop traffic; the lower deck is

much like our avenues, with brightly illuminated shops. Beneath the lower deck

is the level reserved entirely for business vehicles.

Tottenville is

illuminated by electric "suns" suspended from arms on steel towers 200 feet

high. There are also lamps which are just as bright and varicolored as those

that now dazzle us on every Main Street. But the process of generating the light

is more like that which occurs in the sun. Atoms are bombarded by electrons and

other minute projectiles, electrically excited in this way and made to glow.

|

| Housewives in 50 years may wash

dirty dishes—right down the drain! Cheap plastic would melt in hot

water. |

Power

plants are not driven by atomic power as you might suppose. It was known as

early as 1950 that an atomic power plant would have to be larger and much more

expensive than a fuel-burning plant to be efficient. Atomic power proves its

worth in Canada, South America and the Far East, but in tropical countries it

cannot compete with solar power. It is as hopeless in 2000 as it was in 1950 to

drive machinery directly by atomic energy. Engineers can do no more than utilize

the heat generated by converting uranium into plutonium. The heat is used to

drive engines, and the engines in turn drive electric generators. A good deal of

thorium is used because uranium 235 is scarce.

Because of the heavy investment that has to be made in a uranium or

thorium power plant, the United States government began seriously to consider

the possibilities of solar radiation in 1949. Theoretically, 5000 horsepower in

terms of solar heat fall on an acre of the earth's surface every day.

Because they sprawl over large surfaces, solar

engines are profitable in 2000 only where land is cheap. They are found in

deserts that can be made to bloom again, and in tropical lands where there is

usually no coal or oil. Many farmhouses in the United States, are heated by

solar rays and some cooking is done by solar heat.

The first successful atomically driven liners began to run in 1970

after the U. S. Navy had carried on many expensive, large-scale secret

experiments. Outwardly the liners are not much different from the Queen Mary and

Queen Elizabeth, but they have much more cargo and passenger space because it is

no longer necessary to carry about 12,000 tons of fuel.

The metallurgical research that makes the gas

turbines in the power plants and in the trans-Atlantic liners possible has

influenced both civil engineering and architecture. Steel is used only for

cutting tools and for massive machinery. The light metals have largely displaced

it. Ways have been found to change the granular structure so that a metal is

ultrastrong in a desired direction and weaker in other directions. As a result,

the framework of an industrial or office building or apartment house is an

almost lacelike lattice.

|

| Already available is electronic

stove which can prepare meal in 75 seconds. It may replace present

ranges. |

Thanks to these alloys, to plastics and to other artificial materials,

houses differ from those of our own time. The Dobson house has light-metal walls

only four inches thick. There is a sheet of insulating material an inch or two

thick with a casing of sheet metal on both sides.

This Dobson air-conditioned house is not a prefabricated structure,

though all its parts are mass-produced. Metal, sheets of plastic and aerated

clay (clay filled with bubbles so that it resembles petrified sponge) are cut to

size on the spot. In the center of this eight-room house is a unit that contains

all the utilities—air-conditioning apparatus, plumbing, bathrooms, showers,

electric range, electric outlets. Around this central unit the house has been

pieced together. Some of it is poured plastic—the floors, for instance. By 2000,

wood, brick and stone are ruled out because they are too expensive.

It is a cheap house. With all its furnishings, Joe

Dobson paid only $5000 for it. Though it is galeproof and weatherproof, it is

built to last only about 25 years. Nobody in 2000 sees any sense in building a

house that will last a century.

Everything about the Dobson house is synthetic in the best chemical

sense of the term. When Joe Dobson awakens in the morning he uses a depilatory.

No soap or safety razor for him. It takes him no longer than a minute to apply

the chemical, wipe it off with the bristles and wash his face in plain

water.

This Dobson house is not as highly

mechanized as you may suppose, chiefly because of the progress made by the

synthetic chemists. There are no dish-washing machines, for example, because

dishes are thrown away after they have been used once, or rather put into a sink

where they are dissolved by superheated water. Two dozen soluble plastic plates

cost a dollar. They dissolve at about 250 degrees Fahrenheit, so that

boiling-hot soup and stews can be served in them without inviting a catastrophe.

The plastics are derived from such inexpensive raw materials as cottonseed

hulls, oat hulls, Jerusalem artichokes, fruit pits, soy beans, bagasse, straw

and wood pulp.

|

| No more bouts with the razor for a

man of tomorrow. He'll whisk away whiskers with a chemical

solution. |

When Jane Dobson cleans house she simply turns the hose on everything.

Why not? Furniture (upholstery included), rugs, draperies, unscratchable

floors—all are made of synthetic fabric or waterproof plastic. After the water

has run down a drain in the middle of the floor (later concealed by a rug of

synthetic fiber) Jane turns on a blast of hot air and dries everything. A

detergent in the water dissolves any resistant dirt. Tablecloths and napkins are

made of woven paper yarn so fine that the untutored eye mistakes it for linen.

Jane Dobson throws soiled "linen" in the incinerator. Bed sheets are of more

substantial stuff, but Jane Dobson has only to hang them up and wash them down

with a hose when she puts the bedroom in order.

Cooking as an art is only a

memory in the minds of old people. A few die-hards still broil a chicken or

roast a leg of lamb but the experts have developed ways of deep-freezing

partially baked cuts of meat. Even soup and milk are delivered in the form of

frozen bricks.

This expansion of the

frozen-food industry and the changing gastronomic habits of the nation have made

it necessary to install in every home the electronic industrial stove which came

out of World War II. Jane Dobson has one of these electronic stoves. In eight

seconds a half-grilled frozen steak is thawed; in two minutes more it is ready

to serve. It never takes Jane Dobson more than half an hour to prepare what

Tottenville considers an elaborate meal of several courses.

Some of the food

that Jane Dobson buys is what we miscall "synthetic." In the middle of the 20th

century statisticians were predicting that the world would starve to death

because the population was increasing more rapidly than the food supply. By

2000, a vast amount of research has be conducted to exploit principles that were

embryonic in the first quarter of the 20th century. Thus sawdust and wood pulp

are converted into sugary foods. Discarded paper table "linen" and rayon

underwear are bought by chemical factories to be converted into candy.

|

| Inches-deep lake on roof already

cools Southern homes and may become important air-conditioning

method. |

Of

course the Dobsons have a television set. But it is connected with the

telephones as well as with the radio receiver, so that when Joe Dobson and a

friend in a distant city talk over the telephone they also see each other.

Businessmen have television conferences. Each man is surrounded by half a dozen

television screens on which he sees those taking part in the discussion.

Documents are held up for examination; samples of goods are displayed. In fact,

Jane Dobson does much of her shopping by television. Department stores

obligingly hold up for her inspection bolts of fabric or show her new styles of

clothing.

Automatic electronic inventions

that seem to have something like intelligence integrate industrial production so

that all the machines in a factory work as units in what is actually a single,

colossal organism. In the Orwell Helicopter Corporation's plant only a few

trouble shooters are visible, and these respond to lights that flare up on a

board whenever a vacuum tube burns out or there is a short circuit. By holes

punched in a roll of paper, every operation necessary to produce a helicopter is

indicated. The punched roll is fed into a machine that virtually gives orders to

all the other machines in the plant. The holes in the paper indicate exactly how

long a reamer is to smooth the inside of a cylinder, just when a stamping

machine is to pass a sheet of aluminum along to its neighbor with orders to

punch 22 holes in indicated places. There are mechanical wrenches that

obediently turn nuts on bolts and stop all by themselves when the bolts are in

place, shears that know exactly where to cut a sheet of metal for a perfect fit.

Every operation in the plant is electronically and automatically controlled.

|

| Because everything in her home is

waterproof, the housewife of 2000 can do her daily cleaning with a

hose. |

One of

the more remarkable electronic machines of 2000 is a development of one on which

hundreds of thousands of dollars had been spent in the middle years of the 20th

century by Dr. Vladimir Zworykin and Dr. John von Neumann. The purpose of this

improved Zworykin-Von Neumann automaton is to predict the weather with an

accuracy unattainable before 1980. It is a combination of calculating machine

and forecaster. The calculator solves thousands of separate equations in a

minute; the automatic forecaster carries out the computer's instructions and

predicts the weather from hour to hour. In 1950, meteorologists had no time to

deal with the 50-odd variables that should have been mathematically handled to

predict the weather 24 hours in advance.

Following suggestions made by Zworykin and Von Neumann storms are more

or less under control. It is easy enough to spot a budding hurricane in the

doldrums off the coast of Africa. Before it has a chance to gather much strength

and speed as it travels westward toward Florida, oil is spread over the sea and

ignited. There is an updraft. Air from the surrounding region, which includes

the developing hurricane, rushes in to fill the void. The rising air condenses

so that some of the water in the whirling mass falls as rain.

With storms diverted where they do no harm, aerial

travel is never interrupted. And the Dobsons, like everybody else Tottenville,

travel much more than we in 1950—that is, to foreign countries.

By 2000, supersonic planes cover a thousand miles an

hour, but the consumption of fuel is such that high fares have to be charged. In

one of these supersonic planes the Atlantic is crossed in three hours. Nobody

has yet circumnavigated the moon in a rocket space ship, but the idea is not

laughed down.

|

| Forecast of home of tomorrow? This

house was built in few days by pouring concrete into standard

froms. |

Corporation presidents, bankers, ambassadors and rich people in a

hurry use the 1000-mile-an-hour rocket planes and think nothing of paying a fare

of $5000 between Chicago and Paris. The Dobsons take the cheaper jet

planes.

This extension of aerial

transportation has had the effect of distributing the population. People find it

more satisfactory to live in a suburb like Tottenville, if suburb it can be

called, than in a metropolis like New York, Chicago or Los Angeles. Cities have

grown into regions, and it is sometimes hard to tell where one city ends and

another begins. Instead of driving from Tottenville to California in their

car—teardrop in shape and driven from the rear by a high-compression engine that

burns cheap denatured alcohol—the Dobsons use the family helicopter, which is

kept on the roof. The car is used chiefly for shopping and for journeys of not

more than 20 miles.

The railways are just

as necessary in 2000 as they are in 1950. They haul chiefly freight too heavy or

too bulky for air cargo carriers. Passenger travel by rail is a mere trickle.

Even commuters go to the city, a hundred miles away, in huge aerial busses that

hold 200 passengers. Hundreds of thousands make such journeys twice a day in

their own helicopters.

Fast jet and

rocket-propelled mail planes made it so hard for telegraph companies all over

the world to compete with the postal service that dormant facsimile-transmission

systems had to be revived. It takes no more than a minute to transmit and

receive in facsimile a five-page letter on paper of the usual business size.

Cost? Five cents. In Tottenville the clerks in telegraph offices no longer print

out illegible words. Everything is transmitted by phototelegraphy exactly as it

is written—illegible spelling, blots, smudges and all. Mistakes are the

sender's, never the telegraph company's.

|

| Proton microscope under construction

in France probably will magnify objects up to one million

times. |

When

the Dobsons are sick they go to the doctor, in a hospital, where he has only to

push a button to command all the assistance he needs.

In the middle of the 20th century, doctors talked

much of such antibiotics as penicillin, streptomycin, aureomycin and about 50

others that had been extracted from soil and other molds. It was the beginning

of what was even then known as chemotherapy—cure by chemical means. By 2000,

physicians have several hundred of these chemical agents or antibiotics at their

command. Tuberculosis in all of its forms is cured as easily as pneumonia was

cured at mid-century.

It no longer is necessary in 2000 to administer the

purified extracts of molds to cope with bacterial infections. The antibiotics

are all synthesized in chemical factories. It is possible to modify their

molecular structure, so that they acquire new and useful properties.

Even in 1950 physicians did not know exactly how a

piece of beefsteak is converted by the body into muscle and energy—the process

technically known as metabolism. The physician of 2000 knows just what diet is

best for a patient. This knowledge, coupled with his knowledge of hormones,

enables him to treat old age as a degenerative disease. Men and women of 70 in

A.D. 2000 look as if they were 40. Wrinkles, sagging cheeks, leathery skins are

curiosities or signs of neglect. The span of life has been lengthened to

85.

In 1950 little was known about a

virus beyond the fact that it could slip through a filter so fine that it would

hold back any microorganism visible in the optical microscope. The electron

microscope, which magnifies from 30,000 to 100,000 times and which substitutes a

beam of electrons for a beam of light, has changed all this. In the viruses,

little bodies have been detected with this instrument. They are virtually

protein molecules. By tying together what chemists have discovered about the

structure of protein and what the pathologists see in the electron microscope,

such virus diseases as influenza, the common cold, poliomyelitis and a dozen

others are cured with ease.

Even in the

20th century hospitals were packed with instruments and machines. The hospitals

of 2000 have even more. Instead of taking electrocardiographs, doctors place

heart patients in front of a fluoroscopic screen, turn on the X-rays and then,

with the aid of a photoelectric cell, examine every section of the

heart.

Cancer is not yet curable in 2000.

But physicians optimistically predict that the time is not far off when it will

be cured.

|

| Huge aluminum girder is swung about

with ease. Even today light metals replace steel in some

structures. |

The nervous diseases are linked up with electrochemical processes in

2000 in a way that is impossible in our time. Such afflictions as multiple

sclerosis or palsy are no longer regarded as incurable. There are

electrochemical methods of stimulating and reactivating nerves, so that victims

of Parkinson's disease are no longer objects of pity. But these sufferers from

damaged or degenerate nerves are somewhat like our diabetics who must take

insulin regularly to remain alive. A little battery-driven apparatus must be

carried in the pocket to provide the stimulus the nerves need.

Any marked departure from what Joe Dobson and his

fellow citizens wear and eat and how they amuse themselves will arouse comment.

If old Mrs. Underwood, who lives around the corner from the Dobsons and who was

born in 1920 insists on sleeping under an old-fashioned comforter instead of an

aerogel blanket of glass puffed with air so that it is as light as thistledown

she must expect people to talk about her "queerness." It is astonishing how

easily the great majority of us fall into step with our neighbors. And after

all, is the standardization of life to be deplored if we can have a house like

Joe Dobson's, a standardized helicopter, luxurious standardized household

appointments, and food that was out of the reach of any Roman

emperor?