Lord of the Flies

It was said

that Myer Berlow strapped clients into the chair, then David Colburn beat

the stuffing out of them to make millions for AOL.

By Alec Klein

Sunday, June 15, 2003; Page W06

A high-pitched whine emanated from the man at the microphone. Heads turned instantly. The screeching voice, like fingernails running down a chalkboard, was a rude summons back to the main event. Sooner or later, David M. Colburn, he of the slow nasal drawl, was bound to take center stage. As president of America Online Inc.'s business affairs division, Colburn commanded attention wherever he went, which was especially true at his own holiday party that December day in 1999. Besides, he had paid for the festivities out of his own pocket, as he usually did. He had earned the right to grab the mike. Decked out in jeans and cowboy boots, his legs spread wide, Colburn stood on the low platform stage in his airy back yard in Potomac and addressed his business associates, some 80 people who had gathered to celebrate not only the holiday season but also the growing triumph of AOL, the undisputed Internet giant of the land.

Colburn lauded his people -- the deal makers under his charge -- for doing a great job in bringing greater glory to the AOL empire. And then he introduced three men dear to his heart. They were middle-aged, short and dressed casually. Little distinguished them, except this: They were rabbis.

Colburn, who considered himself a devout Jew, asked the three men to join him onstage.

"I brought you here not just because I want to see you," Colburn said. "You're here to help us, to pray for us."

The rabbis seemed happy to oblige. There was a catch, though. With Colburn, associates said, there was always a catch. Sometimes, the catch was a minor clause to his advantage buried deep in a revised contract, a provision Colburn had negotiated for a multimillion-dollar business deal.

But in the matter at hand, the catch was put out there for everyone at the party to witness: The rabbis weren't there just to pray for AOL souls. Colburn wanted them to pray for AOL stock. He offered a deal: If each rabbi agreed to pray for AOL's shares to rise to a certain level, and they hit that level, Colburn promised to donate $1 million to a Jewish cause.

"So you have skin in the game," he explained, cackling.

But Colburn wasn't joking, not about skin in the game. It was a term he favored in his bare-knuckle negotiations when he was extracting millions from companies that wanted to advertise their goods and services on the AOL online service. Colburn, the company's top deal maker, always insisted that AOL's business partners have skin in the game, a vested interest, which usually came in the form of millions of dollars in cash paid to AOL. That would make AOL's business partners work harder to make the relationship with AOL work. If they had something at stake, like their financial survival, they would perform. Same with the men of faith. If the rabbis had something on the line, they wouldn't just be praying for Colburn's soul.

He would have skin in the game, too. If the rabbis' prayers were answered and AOL's stock did rise, Colburn would be out a cool $1 million. Not that he would miss it. He was already a multimillionaire -- some put his net worth at more than $250 million -- which he had earned mostly through stock options. It was the way legions at AOL minted money back then: Stock options gave Colburn, as they did other employees, the right to buy AOL stock at a certain price in the future. The idea was to wait until the stock rose above that price, buy the stock at a discount thanks to the options, then turn around and sell it at the going market rate and reap a huge profit.

Lord willing, AOL stock would rise high enough that Colburn would make enough to donate $1 million to the rabbis, with plenty to spare. The stock was a pretty sure bet. The way AOL's stock was ticking up, up and away, reaching beyond $90 a share that December, he didn't exactly need God's help.

Then again, why take chances?

One rabbi, however, wasn't completely sold on the deal.

Apparently sensing that Colburn was open to further negotiations, the rabbi offered a counterproposal. He said he would pray for AOL's stock to rise only if Colburn started showing up at synagogue. Colburn acceded, and the three rabbis agreed to pray for AOL's stock to rise.

Colburn, as usual, won the negotiation.

Together, the rabbis offered their blessings and thanks, while Colburn stood by, pious and grave, his eyes shut, wishing, perhaps, for a big payday, spiritual or otherwise.

It was a stunning moment, a surreal confluence -- if not an unholy alliance -- of religion, greed and the intoxicating whiff of power that lay in AOL's grasp at the height of the Internet boom of the 1990s. Some said they were appalled by the prayer. And yet no one uttered a word in protest. It wasn't the place, not before dozens of Colburn's closest associates. Besides, who wanted to incur the notorious wrath of David Colburn?

"How do you pray for the stock to go up?" wondered an AOL official in attendance. "It's ridiculous."

And yet, Colburn, a man of his word, was soon thereafter found in a Jewish temple, cleaning a rabbi's office. Apparently, the deed did not go unheeded. AOL's stock, continuing to soar in those days of the Internet star, hit the mark.

There was so much to David Colburn, all of it so outrageous and comical and scary and brilliant and successful and charitable, that he almost defied human description. And yet there he was, an open book, a raging, exploding caricature of a personality, a combustible force of nature. It was who Colburn was, or wanted to be, or couldn't help being.

At AOL, his stature grew to such epic proportions that he earned a nickname: God.

This was not your typical deity. To begin with, there were his black cowboy boots, emblazoned with the AOL logo. Colburn's sense of fashion leaned toward jeans and tank-top undershirts in an I-don't-care-what-the-hell-you-think manner of dress that he displayed at important company meetings. Grizzled and rumpled, he might wear a T-shirt boasting a cartoon character under a green glen-plaid suit jacket. Some tossed it off by saying he was just an eclectic dresser. Others said he was simply a bad dresser. Eventually, friends persuaded him to get rid of the so-called wife-beater undershirt look. It didn't play well, not even in the hypercasual milieu that was AOL.

"He's like the older guy in a boy band," said a former AOLer who worked for Colburn. "He wants to be hip and cool, but it's not cool anymore because you're in your forties."

Colburn also favored the five o'clock shadow look, as if to remind others that he was too busy for such minutiae as personal grooming. But apparently he did care. Otherwise, why would he brag to his friends about the dark hair plugs he got from South America to cover up his balding head? He combed his hair forward, and yet he would make cracks about other AOL executives who were losing their hair. Some thought there was an implied strategy in that: Attack first, strike first.

The man was a walking contradiction, a towering figure except for that squeaky squeal of a voice, which some believed he exaggerated for effect and at which even Colburn himself poked fun.

"There's a lot of disparities to David Colburn," said a former AOL official who worked with him. "He's like Tony Montana from 'Scarface' meets Andy Warhol."

So there it was -- the ruthless gangster with the effete sensibilities. Who knew this was the man of the moment? The king at AOL was supposed to be Steve Case, the company chairman and chief executive, or so the public was led to believe throughout the 1990s. Case was that boyish, clean-cut pitchman from the Gap ads in crisp khakis and denim button-downs. Case did steer the prodigious AOL ship, but he didn't actually operate the levers and switches. He served another purpose -- that of the public face of AOL, marketing the service as clean family fun. It was all geared to that wholesome purpose, including the cheerful voice that greeted consumers when they signed in to their AOL accounts: "You've got mail!" Or the cartoonish icons that populated the AOL service, like the little stuffed mailbox, the edges rounded, the colors bright and cheery. It was designed to be innocuous, simple -- so simple, in fact, that critics came to call it, derisively, "the Internet on training wheels."

But behind the unthreatening image, another dominated at AOL's Dulles headquarters: the menacing visage of David Colburn.

The cowboy executive came to personify the aggressive company as it hurtled into the wild, throbbing heyday of the late 1990s and the turn of the 21st century. Even more, Colburn came to epitomize the brash dot-com culture that pervaded the entire industry.

Officially, Colburn's title was president of business affairs, overseeing a group of deal makers who were in the middle of many of the company's biggest and most complicated transactions. Usually the deals involved selling online advertising space, those rectangular "banner" ads that appear on people's computer screens when they are logged on to their AOL accounts.

Unofficially, though, Colburn was known as Steve Case's and Bob Pittman's muscle. While Case ruled AOL, thinking big thoughts about future technology, Pittman ran the day-to-day show as company president, pushing aggressive financial targets for AOL. Colburn was their go-to guy. He pushed the buttons. On big deals, when AOL was negotiating multimillion-dollar contracts, it was left to Colburn to extract the last dollar, to bend the other side to his will.

Through his attorney, Colburn declined to be interviewed about his business and personal affairs. But friends and colleagues described him as an enforcer from an unlikely background. He was the son of a well-to-do toy manufacturer in the Milwaukee suburbs, in a family whose annual traditions included buying a new Cadillac. As a boy growing up in the 1960s, he liked basketball, a game he played with ferocity, much as Steve Case did in his own youth. When Colburn didn't like a call, he'd get into an opponent's face. Or he'd just foul him. A lot. And hard. That brazen style carried over when he became a West Coast corporate lawyer, although little about Colburn's professional life pointed to a dazzling future. For more than a dozen years, he remained an associate in a law firm without getting elevated to partner. But when he joined AOL in 1995, he quickly established his credentials as an effective deal maker.

Less than a year into the job, he negotiated a seminal deal to get the AOL icon on Microsoft's Windows start page, valuable real estate on the computer desktop because it suddenly gave AOL access to untold millions of Microsoft customers who might sign up for the online service. With the deal, AOL wouldn't have to send free disks to get people to sign up. The software would be preinstalled in the computer.

Colburn employed an effective technique to broker the deal. Some called it a club. He threatened to use the Netscape software browser if Microsoft didn't agree to put the AOL icon on the Windows start page. Microsoft, apparently fearful that Netscape's browser could topple the Windows operating system hegemony in the personal computer world, agreed. For Colburn, it was a beautiful thing. AOL didn't have to pay a dime to its arch-rival for the prime placement. Instead, AOL agreed it would adopt the Internet Explorer browser, Microsoft's software program.

With that deal, Colburn cemented his reputation at AOL.

Not that he rested on his laurels. Colburn knew the specific details of a contract negotiation better than anyone else. He took the time to rehearse. He read prodigiously and remembered effectively. He was devoted, e-mailing people at midnight to review particular details. Colburn was disarmingly frank as well, knowing when to ask for exactly what he wanted out of the other party. He also knew when to go for the jugular. His was often a bone-jarring negotiating technique that was filled with swearing and threatening. During one phone call in his office, he was heard yelling at someone, belittling him, tearing him down, screaming, "Don't be a [f-word] idiot!"

Someone who happened to be passing by asked another bystander whom Colburn was talking to.

"A client," came back the answer.

The threat of David Colburn became so powerful that it inspired fear well beyond Dulles, all the way to Silicon Valley, among would-be partners of AOL. Few wanted to get in the ring with him.

"David had such a reputation that you could always use his presence as a threat," said Neil Davis, a former AOL senior vice president. "It was like, 'If we can't get over this issue, we have to get David on the phone.' I could always invoke David as the court of appeals."

Colburn, for all his power, could also be a big teddy bear. "Yes, he swears, screams and yells, but he also gives millions to religious Jewish charities," said a close associate who has known Colburn for years. "Though he's gruff and though he's pushy and he's got one of the worst personalities for this, he cares more about people than I do even. That's the truth."

Another friend said Colburn quietly gave his company driver, who refused to borrow money on religious principles, a considerable sum of cash to buy a house and a car, no strings attached. "His persona was a kicker and a screamer and an [expletive], but there was another side," said another close colleague. "David was capable of being an incredible softy."

A former AOLer put it this way: "There are times when you almost think he's human."

Colburn professed to be mystified by his reputation for being overbearing. Once, while sitting in plush leather seats in the spacious company jet, his fellow AOL executives seemed comfortable enough finally to confront Colburn with an uncomfortable question: How could he be so mean?

"I'm a nice guy," he insisted in his high-pitched tone. "I don't get it."

Colburn loved to indulge his children. In June 2000, he celebrated his daughter Rachel's bat mitzvah by hiring one of the hottest boy bands on the planet: 'N Sync. The party favor reportedly cost $1 million. Nearly two years later, in March 2002, Colburn pulled out all the stops for his other daughter, Jessica, at her bat mitzvah party, paying $35,000 to rent much of the ground floor at Washington's Union Station. The featured attraction was rock star Dave Matthews. How much this cost was not revealed. Jessica's shindig also featured boxing promoter Don King and a Las Vegas theme, including a casino with fake $100 bills bearing her picture.

Colburn and his prodigious parties became industry lore. They even made it into an episode of HBO's popular sitcom "Sex and the City," when Samantha, one of the main characters, was hired as the publicist for a wealthy girl's bat mitzvah. After Colburn learned of this apparent reference to his own familial indulgences, he screamed, he cursed, and then he called up a bigwig at HBO and ordered 50 copies of the episode.

When Myer Berlow started playing with the knife, Neil Davis knew there was a problem.

Davis was giving a business presentation in mid-1998 in a small Seattle conference room when he noticed Berlow, his boss, fidgeting. Berlow, the head of AOL's advertising division, was bored and tapping the knife impatiently on the surface of the conference table. Not a good thing. In fact, it was downright unnerving.

"The blade was six to eight inches long," Davis reckoned, from a glance out of the corner of his eye.

"It wasn't a hunting knife," Berlow recalled. "It was a pocket knife."

Colburn, who was also in the room, didn't seem bothered by the glint of the knife. But the other person there, Jeff Bezos, the chief executive officer of Amazon.com, appeared alarmed.

"Bezos's eyes became the size of saucers," Davis said.

Things were not going as planned. AOL was trying to pitch Amazon, the emerging online retailer, on the benefits of advertising its goods on AOL. But Davis, a compulsive contrarian, had other ideas. He had always wanted AOL to buy Amazon. He had even crunched the numbers, massaged the idea and thought of selling off Amazon's warehouses to save money. He was convinced that the retailer, a growing force in electronic commerce, would be one of the online survivors. He wanted it to be a part of the AOL universe. Which was why Davis included the slide that Berlow and Colburn had explicitly warned him not to use, the one about how Amazon should be integrated within the AOL service. Amazon, Davis explained to Bezos, should have its own "tab," marking it clearly for consumers within the AOL shopping section of the Web site.

"That's moronic," Colburn sputtered, then turned to Berlow. "What the hell is Neil doing?"

Berlow glared at Davis, pointing the knife at him. "If you don't take that slide out," he said, "I'm going to stab you."

Berlow appeared serious. He was not only pointing the knife at Davis, he started approaching him with the weapon. "Bezos thought I was going to get stabbed," Davis said.

He didn't. But he did shut up, and AOL went on to strike an ad deal with Amazon.

Berlow couldn't explain why he took out the knife that day. Then again, there was much about Myer Berlow that was mystifying, if not a bit zany.

Maybe it was something in the water. Berlow, as it happened, was raised in the same neighborhood as Colburn, a Jewish suburb of Milwaukee. Berlow not only knew Colburn, who was about 10 years his junior, but was also best friends with Colburn's older brother.

The oldest of six children, Berlow was born in Cambridge, Mass., and grew up in a farmhouse across the highway from Colburn's home. Berlow was the precocious son of a physician, a voracious reader who became politically active in the 1960s and 1970s, studied Russian at the Leningrad Polytechnic Institute in the summer of his junior year of high school, and then went off to Kenyon College to major in religion. All of which apparently prepared him for a career in advertising.

When Berlow joined AOL in 1995 as vice president of national accounts, he already had 20 years of experience working at ad agencies in New York, L.A. and Miami. Few in Northern Virginia, where fashions tended to lag behind those cities, were prepared for the razzle-dazzle of Berlow: the black Armani suits, the indigo button-downs, the black and silver ties, the dark hair drawn back in a ponytail, the frenetic pace.

He was constantly on the go, beginning at 6:30 a.m., when he could be found sweating on a StairMaster in the company's basement gym, while reading a book. A colleague, perspiring at an adjoining StairMaster, once asked him what book he had chosen. He said he was reading about ADD, attention deficit disorder.

"Oh, yeah, my brother has that," the colleague said.

"Oh, I had that, too," Berlow responded. "But I'm better now."

It seemed an odd confession, though apparently not to Berlow. And not to the colleague after she got to know him better. "That makes sense now," she said. "What you see is what you get."

Berlow didn't try to pretend. In the thick of negotiations with top executives of another company, he once played video games on a handheld device. During a meeting with Sony executives in Tokyo, he tossed aside polite convention and requested that they give him two PlayStation video consoles because they were impossible to get in the States. While Colburn bragged about his hair plugs, Berlow boasted about his own personal makeover: plastic surgery to remove wrinkles under his eyes, and caps on his teeth. His favorite movie was "The Godfather." His philosopher-hero was Machiavelli, whom he liked to paraphrase: "Whether it is better to be loved than feared or vice versa: My view is that it is desirable to be both loved and feared; but it is difficult to achieve both, and, if one of them has to be lacking, it is much safer to be feared than loved." To which Berlow would add, "Machiavelli has been given a bad name."

Berlow read science and history, owned his own plane, had a gun license in Idaho, and couldn't resist the lure of eBay, on which he successfully bid for a 1969 Mercedes. His buying sprees got so out of hand that the boxes shipped from eBay piled up in his office, many unopened. He couldn't bring them home; his wife would kill him. So in the middle of meetings, he would start pulling out jackets and other clothing he had acquired through auctions, handing them out to his staffers to try on for size and take home. During the holidays, his secretary would toss an expensive catalogue to numerous colleagues and tell them to pick out whatever they wanted. It was on Berlow.

Among the rich at AOL, Berlow was one of the richest, so rich in fact that he seemed almost numb to money. On a trip to Las Vegas in 2000, he barely noticed when he was down $60,000 while playing blackjack by himself against the dealer at the high-roller table at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino.

"He says it's a Zen activity for him," said a colleague.

Playing quickly, he reversed his losses and walked away with about $130,000. As he was heading back to his suite, he tried to hide his winnings by shoving wads of cash down his pants.

He was generous. He was brilliant. Many AOL women thought he was the best-looking man on campus. "He's so charming that even if you know he's not telling the truth, you smile and accept it anyway," said Randy Dean, who worked as Berlow's right-hand man in building AOL's advertising business in the mid-1990s.

Berlow also rubbed people the wrong way. Mark Walsh, a former senior vice president, called Berlow "an acquired taste." Part of the problem was the company culture. When he arrived in 1995, Berlow was trying to turn AOL from a subscription-based business into an advertising medium, and some of the AOL computer programmers turned their noses up at the idea. Advertising on the Internet? What a crass idea. In those days, AOL fostered independence, and some programmers took that for gospel, refusing to post the ads that Berlow had sold on the online service.

Like the programmers, Steve Case hated the idea of sullying AOL with a bunch of online ads. It wasn't consumer-friendly. Case said as much during a staff meeting in the mid-1990s, according to sources in attendance. Berlow had just persuaded Sprint to buy $5 million in banner ads that would run across the bottom of the Web page.

"I don't like it," Case said.

Berlow reminded the CEO that Sprint, the big telephone company, was going to pay $5 million.

Case was unimpressed. "What really bothers me," he said, "is the ads are in a place where members will see them."

"You don't really mean that," Berlow said. Case did. Berlow exploded: "Are you out of your [f-word] mind? You used to work for Procter & Gamble! How much would they pay for ads that nobody would see?"

Offended, Case stormed out of the room and asked Ted Leonsis, then running the online service, to fire Berlow. Leonsis, who understood Berlow's value, declined. Case let it go.

After a while, Case appeared to accept Berlow, just as he seemed to tolerate Colburn. Case left it largely to Leonsis, and then his successor, Pittman, who became AOL's president in 1996, to deal with the two colorful executives. Sometimes, though, it was hard to distinguish Berlow from Colburn. Some called them "the terrible twins." Not only had they grown up together, they were fast friends as adults when they weren't screaming at each other. Colburn, the attorney, helped review Berlow's divorce papers. Neither wanted the other promoted first; they were simultaneously promoted from senior vice president to president of their respective divisions in 1999. "He [Colburn] and Myer are like Frick and Frack. What one gets the other wants," said one AOLer who worked with both men. "Myer and David are alike. Myer's just a better dresser."

Berlow played good cop to Colburn's bad cop when negotiating with other companies. As AOL's top salesman, Berlow was supposed to woo clients. As AOL's top deal maker, Colburn was supposed to get the best possible terms. The joke around the company was that Berlow strapped clients into a chair, and then Colburn beat the stuffing out of them.

Before the strangling and the death threat, the meeting in Dulles began innocently enough.

Colburn sat back while Berlow reviewed a proposed deal with executives of Music Boulevard in 1997. It was supposed to be a slam-dunk. Colburn and Berlow had already gone through the numbers. They had done the calculations. Music Boulevard, an online music service, was going to pay $8 million over three years to run ads on AOL.

Except, Berlow said, he was suddenly hit by an epiphany: It occurred to him that, at $8 million, Music Boulevard was getting a good deal. No, not good. Great. He and Colburn had based the price of the deal on assumptions about how much in sales and profits Music Boulevard would derive from the ads it bought from AOL. And yet, right in the middle of this meeting, even as they were dotting their i's and crossing their t's, it dawned on Berlow that there was an entirely different yardstick by which this deal should be measured: If Music Boulevard launched an initial public offering of stock -- and its parent company, N2K Inc., had already filed a registration statement with the Securities and Exchange Commission to do just that -- then an ad deal with AOL, already emerging as the industry leader, would be worth much more than $8 million. Call it gilt by association. AOL was golden; thus, Music Boulevard would be golden, too. Racing through Berlow's mind was an appalling notion: Backed by an AOL ad deal, these Music Boulevard executives stood to personally gain millions from an IPO! And AOL wouldn't get a piece of that!

Berlow quietly tore out the pricing page from the proposed contract: That $8 million figure soon vanished in a crumpled piece of paper in his fist. Then, dashing off a quick calculation in his head, he threw out a number on the fly. "The price is supposed to be $16 million," he recalled saying.

The Music Boulevard executives were perplexed. This was a final review of the contract, to which they had already agreed. And the price tag was $8 million. Colburn threw a scathing look at Berlow, then tried to salvage the situation, turning to the Music Boulevard executives. "Myer is saying it's worth $16 million, even though we're asking for only $8 million," Colburn explained.

Berlow, unmoved, corrected Colburn, insisting that he did mean $16 million, not $8 million.

Berlow could see Colburn's staffers fidgeting. Rising from the table, Berlow said he needed to go to the bathroom, and he asked a seething Colburn to join him. A new Colburn hire, on his first day at AOL, tagged along. As they moved out into the hallway, the new hire broke the silence by beginning to say, "I think -- ," before Colburn snapped back, "What did you say?"

Glaring at the new hire in his Brooks Brothers suit, Colburn barked, "How long have you been here? I don't give a [f-word] what you think! Shut the [f-word] up!"

Then, he turned his death glare onto Berlow. "The deal," Colburn snarled, "was supposed to be $8 million, not $16 million." Berlow hissed that he knew that. Berlow proceeded to explain why he had doubled the price, then yelled at Colburn for being a complete idiot for not picking up on his implied cues. "Since you [f-word] up the sale, David," he said, "every dime under $16 million you should pay out of your own pocket!"

Colburn snapped. Grabbing Berlow by the throat, Colburn rammed him against the wall, screaming, "I'm going to kill you!"

Berlow was instantly overcome by tears -- of laughter. Colburn, befuddled, loosened his grip on Berlow's neck. Why are you laughing? he asked. You're not even scared.

"Well, David, I knew you couldn't do anything," Berlow retorted. "I could beat the crap out of you."

The only thing Berlow said he was afraid of was that Colburn would hit him in the face, and the mark would show when they went back into the room to finish the deal with Music Boulevard.

The chastened new AOL hire said, "Oh my God."

He gazed at Colburn and Berlow as if he were wondering how he had so utterly ruined his career by taking this job. Colburn and Berlow, no worse for the wear, reentered the room. In the end, they didn't get $16 million. They got $18 million.

AOL also got a cut of Music Boulevard's sales.

Berlow and Colburn had prevailed. Online advertising was AOL's engine of growth. By late 1996, it had become clear that AOL faced a threat to its very existence -- stiff price competition from other Internet service providers. The company responded by abandoning the hourly fee that it had been charging customers, replacing it with a flat-rate monthly charge. Users, however, began to spend more time online, taxing AOL's network and eating into its profit margin.

With Colburn and Berlow at the controls, advertising deals quickly picked up the slack. In spectacular fashion, revenue from advertising and commerce (including fees from online transactions) rocketed from virtually nothing at the time Berlow and Colburn arrived in 1995 to more than $2 billion in 2000 -- about a third of the company's overall revenue -- largely because of their handiwork. Through brute force and key strategic decisions, Colburn and Berlow helped reshape AOL from a one-dimensional online service dependent on subscriptions into a major advertising force in the mass media.

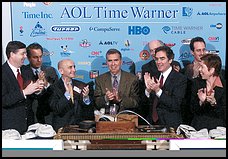

When AOL announced its blockbuster takeover of Time Warner Inc. in January 2000, the mania was in full swing. Start-ups were lining up to strike a deal with AOL. Two factors were at play: Dot-coms were rich with venture capital and clamoring to promote themselves. Second, a big advertising deal with AOL was considered the ticket to respectability for dot-coms taking their stock public. And for good reason: In 2000, 45 percent of all U.S. households using a telephone dial-up connection subscribed to AOL or its subsidiary, CompuServe. What's more, four out of five Americans surfing the Web inevitably reached an AOL site, whether it was MapQuest, the popular tool for driving directions, or Moviefone, the online ticketing service.

The company, as Steve Case had envisioned in what he called his "AOL Everywhere" strategy, was indeed becoming ubiquitous. It was also becoming enormously powerful. Dot-coms weren't just hoping to give AOL their money, they were pleading.

In early 2000, for example, AOL pitted Homegrocer.com against Webvan Group, two online supermarkets, in a competition to see who would pay AOL more to promote its service. One would win; the other would be left to find a way to promote itself on the Web. Homegrocer apparently wanted AOL more. Even though the dot-com was actively marketing its online grocery service in only two cities at the time, it agreed to pay AOL $60 million over five years, a staggering sum. AOL, in turn, agreed to give Homegrocer exclusivity on its online service, shutting out Webvan. Homegrocer wasn't just banking on beating out Webvan; it figured its massive promotions reaching AOL's millions of subscribers would make its IPO that much more attractive. But by paying AOL so much upfront, it couldn't survive. Instead, Webvan ended up buying Homegrocer. Then it, too, went kaput in July 2001. AOL officials weren't particularly sympathetic. Besides, there was little chance that AOL could talk dot-coms out of these deals, even if it wanted to -- not at the height of the frenzy.

"We have all these people walking through the door with cash. The question is, where do we put them?" said Dave Sickert, former director of AOL's online shopping service. "You had so many people walking through the door with wads of cash. It was life or death to them if they couldn't cut a deal with AOL. It was ludicrous."

By the late 1990s, Colburn's business affairs division was a hard-charging unit of a hundred or so deal makers, including many lawyers, who toiled in an obscure building -- Creative Center 4, or CC4 -- across the street from Dulles headquarters. And yet, for all its distance from the focal point of corporate power, the hand of business affairs was felt far and wide. Within the company, the prevailing belief was that business affairs -- known simply as BA -- held considerable sway over other departments, if only because it negotiated and finalized most of AOL's largest transactions.

BA was the heavy artillery brought in to close a transaction. Colburn's deal makers usually got involved in advertising deals after the sales force had reached a general agreement with clients. Business affairs officials would draw up a list of proposed terms, extracting as much as they could and then reviewing the fine points of the deal structure with the company's accountants. The unit's work was also blessed by executives at the highest levels, including Pittman, the AOL president, to whom Colburn reported. But there was no mistake about who was calling the shots. Business affairs deal makers answered to one person only: David Colburn.

Those who worked for him dreaded his weekly staff meetings. These were supposed to be times to brief him on the status of business deals, to walk him through the terms of a complicated transaction. Instead, they often turned into times for Colburn to second-guess his troops, to puncture holes in their thinking. Rarely did they walk him through an entire deal. It usually didn't get that far. While they were talking, he would flip through the pages, appearing not to listen, then stop and suddenly ask about a specific detail -- oftentimes a detail from an earlier version of a contract from a week before. "An inane detail," said one of his deal makers. "He could always find something you don't know the answer to."

To win his favor, many young deal makers not only sought Colburn's approval, they became him. At one of his parties, some of his underlings dressed up as Colburn, wearing cowboy boots and a T-shirt. That, however, was just a lark. It wasn't so funny when the mimicking spilled over into the office, as a cadre of Colburn storm troopers marched about in similar garb, needing shaves, swearing and cursing at colleagues, rudely interrupting people from other divisions during company meetings. Some even adopted his high-pitched honk of a voice. Or they just screamed like he did.

Colburn set the tone at AOL, but some feel the sense of urgency would have prevailed there anyway, albeit at a lower decibel level, even if he hadn't been there. In the 1990s and into 2000, AOL was leading the way in the evolution of a new medium, trailblazing an Internet vision amid the pressing realities of Wall Street, which kept demanding immediate financial results from the online firm.

"We didn't have the niceties of time," a former executive said. "Tensions were high. It was really hard and the pressure was intense and the pressure was continual . . . Deals were getting done quickly, and they were hugely important to the company. Wall Street was getting impatient with the company, and that is no lie, so the pressure was there."

Colburn, though, ratcheted up the pressure even more, encouraging a hyperaggressive atmosphere, and many of his charges took his cues, fighting even among themselves over the pettiest of issues, such as who had the bigger office. In one instance, two vice presidents were promoted to senior vice president at around the same time in the late 1990s. But when they got new offices, one executive suspected an inequity. He pulled out blueprints and measured the square footage of each office. His suspicions were confirmed when it turned out that the other guy's office was bigger than his by a few feet.

"He blew a gasket," said a former employee who worked with him.

Walls were moved, and his office was reconfigured to make it as large as his counterpart's.

It became the BA way. Yield nothing, no matter how small. Suddenly, deal makers weren't negotiating; they were demanding. "I would joke I'm a mafia enforcer," said a former deal maker. He would approach prospective clients, tell them what to do, and then say, "Do we have an understanding? Capisce?"

Usually, they did.

"It was very real, the cowboy arrogance," said a former AOL executive. "It was very much inherent in the culture: 'We're AOL, we can screw people. We will squeeze every last dime out of you because of who we are.' "

Sometimes the arrogance went so far that even Colburn put on the brakes. Such was the case in the late '90s when a new deal maker tried to make a good impression on the boss. During a weekly staff meeting, the new guy explained that he had negotiated a $5 million ad deal with a dot-com, but he was convinced he could get more. As a matter of fact, he told Colburn, he had already been working to squeeze twice as much out of the dot-com.

Colburn, however, was already aware of this. The dot-com had called Berlow, the top AOL sales executive, to complain about how much pressure was being applied by this new deal maker. Berlow, who was also sitting in on the meeting with Colburn, told the young deal maker to settle for $5 million. But the newcomer wouldn't hear of it. He had done his homework, the dot-com was a public company, he knew how much money it had in the bank, and he was convinced its board of directors would approve a $10 million deal.

"Look, they can afford $10 million," he insisted.

Berlow countered, "I can afford a Rolls, but I'm not going to buy one."

"I can, too," the deal maker shot back.

Colburn, enjoying the scene, chuckled. Then he weighed in: The deal was $5 million, end of discussion. Colburn, however, couldn't resist smiling approvingly at his new charge.

"He was like the proud father looking at the lion cub who has his first kill and is all excited about it," recalled the newcomer.

The aggression, however, didn't sit well with others. Randy Dean, for one, was disturbed when he witnessed brash deal makers at work, orally beating up on business partners. "I definitely saw that at meetings," he said. "They weren't always nice about it." Afterward, Dean, then an AOL advertising executive, would catch up with the deal makers and try to explain to them why "strong-arm tactics" weren't always a good idea. He tried to appeal to logic. AOL, he stressed, would have to work with these companies after striking a deal with them. It was only the beginning of what AOL hoped was a long-term relationship. Why start off on the wrong foot? Not to mention that such arrogance didn't put AOL in the best possible light with other prospective business partners.

Sometimes, Colburn's deal makers listened. Sometimes, they didn't. "Who cares?" said one. "We're making money."

By late 1999, many companies seeking to do business with AOL were no longer viewed as potential partners. They were a target, to be used. The first order of business was for AOL deal makers to find out how much money the dot-coms had raised in venture capital funding, then try to extract as much as possible from them in online ad deals. Informally, AOL's goal was to get a minimum of 50 percent of a dot-com's venture capital funding.

" '[F-word] 'em,' that was our mantra," said an AOL official. "We'd say that all the time. We took it to heart. 'Destroy them. [F-word] 'em.' You lived by that."

In negotiating deals with companies, another AOL official said, the aim finally reached this basic level: annihilation. "When we walked away," he said, "they wouldn't remember their own names. It was crazy. It was the high of the deal. It was the high of the battlefield."

It was part of the full-throttle approach of BA, which spawned a whole series of effective but brutal techniques normally reserved for unwitting dot-coms.

The first gambit many deal makers learned was this: "You make a mistake" on purpose, said one versed in the art. To wit: When trying to pitch the virtues of advertising on AOL, a deal maker would offer a PowerPoint presentation to a prospective client. One of the slides, however, would include the logo of the client's rival, as if AOL had accidentally mixed up some of the slides from another presentation. The deal maker, pretending to be embarrassed, would apologize profusely. It was intentional, of course, and often it achieved the desired effect. It would seem that AOL was negotiating a similar deal with the client's rival, which would spur the client to act first.

"Another thing we'd do is create an insane deadline," said an AOL official. "We called it 'the crunch time.' " It would start out as a slow waltz between AOL and a prospective client, involving lots of wooing and pretty words about how great the client's business was, how neat it would be if the two sides hooked up, how wonderful it would be if the client bought ads on AOL.

Naturally, AOL wouldn't mention that it was having precisely the same slow dance with multiple partners. Weeks would go by -- then AOL would suddenly demand immediate action. Abruptly, deal makers would draw up a contract, slam it on the table and order the prospective client to sign it within 24 hours or, worse, by the end of the day, or else AOL would take the offer to another party, which happened to be standing by -- "even if it's all [expletive]," said an AOL official.

What had begun as a delicate courtship would end up with an ultimatum that would leave the client reeling -- and usually agreeing.

One company called dealing with AOL "trench warfare." Deal makers produced mammoth contracts the size of telephone books and even harder to get through -- and then waged hand-to-hand combat over the specific language contained in them. AOL executives also made officials of other companies sit around for hours, in a so-called waiting game, just to let them know they were not important.

When all else failed, AOL deal makers sometimes concocted a fiction to drum up business. That happened in early 1999 when AOL was mired in a long-term deal with Preview Travel, an online travel agency that showed little promise. Preview Travel had little financial backing, its online content was sparse, and AOL, which owned a small equity stake in the firm, wasn't getting much in the way of ad revenue -- $18 million over seven years, tops, said former ad executive Neil Davis.

So he devised a plan to get out of the deal: Get somebody to buy Preview Travel. "I came up with the idea," he said. First, he massaged the idea with Eric Keller, a business affairs executive, to make sure "it didn't sound like some sort of drug-induced hysteria," before he ran it by the higher-ups. There was only one hitch: Nobody was interested in buying Preview Travel. With the help of colleagues, Davis said, he created the illusion that someone was courting the small travel firm. "I made it up," he said. "I basically created a situation where people thought that Preview Travel was on the block and that AOL was going to be supportive of a long-term deal with the new partner."

What Davis didn't account for was this: Microsoft, AOL's nemesis, arrived on the scene, kicking the tires to see about buying the little online travel business. Davis, a hard-wired AOLer who couldn't countenance the idea of having anything sold to Microsoft, quickly scrambled to see if the parent company of Travelocity, another online travel service, was interested in making the purchase. It was, and before long a deal was done. AOL got out of its deal with Preview Travel, and in the process, Davis pulled off a gargantuan ad coup, getting the new owner, Travelocity's parent company, to agree to a $200 million, five-year deal.

"It was," he said, "the perfect scenario."

Through such aggressive deal making, AOL grew to great proportions, reaching the pinnacle of its power when it acquired Time Warner. But the bruising techniques and negotiations left a string of financially hobbled dot-coms that eventually couldn't pay their bills. Many would die soon.

So would some AOL executives' careers.

On July 24, 2002, AOL Time Warner Inc. disclosed that the SEC had launched a civil investigation into its accounting practices, based on a series of articles published by The Washington Post. Less than a week later, AOL confirmed that the Justice Department had opened a criminal investigation into the company's accounting. Meanwhile, AOL launched its own internal probe.

For Colburn and Berlow, the trio of investigations signaled a potential problem: Both men were involved in many of the transactions under scrutiny, a slew of complex and exotic deals in which the company inflated its advertising revenue to make its financial results look better than they were. Berlow and his crew had helped bring in the deals, Colburn had signed off on them.

Quickly, the two executives retained counsel in connection with the federal probes. Attorneys, however, could not stave off the inevitable: On August 9, Colburn was locked out of his office at Dulles headquarters and fired. And Berlow was squeezed out of an operational role, negotiating a job as a company consultant that left him with little to do. Meanwhile, business affairs -- Colburn's infamous band of aggressive deal makers -- was dismantled, with its employees dispersed to different departments across the company. Then, on October 23, 2002, AOL Time Warner said it would revise its financial results for a two-year period occurring before and after its merger in January 2001 to account for online ad sales and other deals that improperly inflated revenue by $190 million.

That, as it turned out, was the cost of bending the rules. The cowboy days were over.

Alec Klein is a reporter for The Post's Business section. This article is adapted from Stealing Time: Steve Case, Jerry Levin and the Collapse of AOL Time Warner. Copyright 2003 by Alec Klein. Published this month by Simon & Schuster. Klein will be fielding questions and comments about this article at 1 p.m. Monday on www.washingtonpost.com/liveonline.

© 20